Bottom Line

I believe an investment in Fever-Tree Drinks PLC (AIM:FEVR) (Fever-Tree) represents an opportunity to buy an overlooked consumer products franchise. Fever-Tree is the dominant player globally in the premium mixer market and has the number one position in the United Kingdom, Europe, and the United States for key products. The company has been negatively impacted by decelerating alcohol volume trends, a weaker consumer environment, and substantial cost inflation. As a result, the share price has fallen approximately 70% from its peak in 2021, creating an attractive opportunity today. The business is in the process of rebuilding margins through production localization, cost optimization, and organic growth. Fever-Tree has successfully continued to adapt its portfolio away from tonics, providing evidence of the firm’s adaptability to local market preferences.

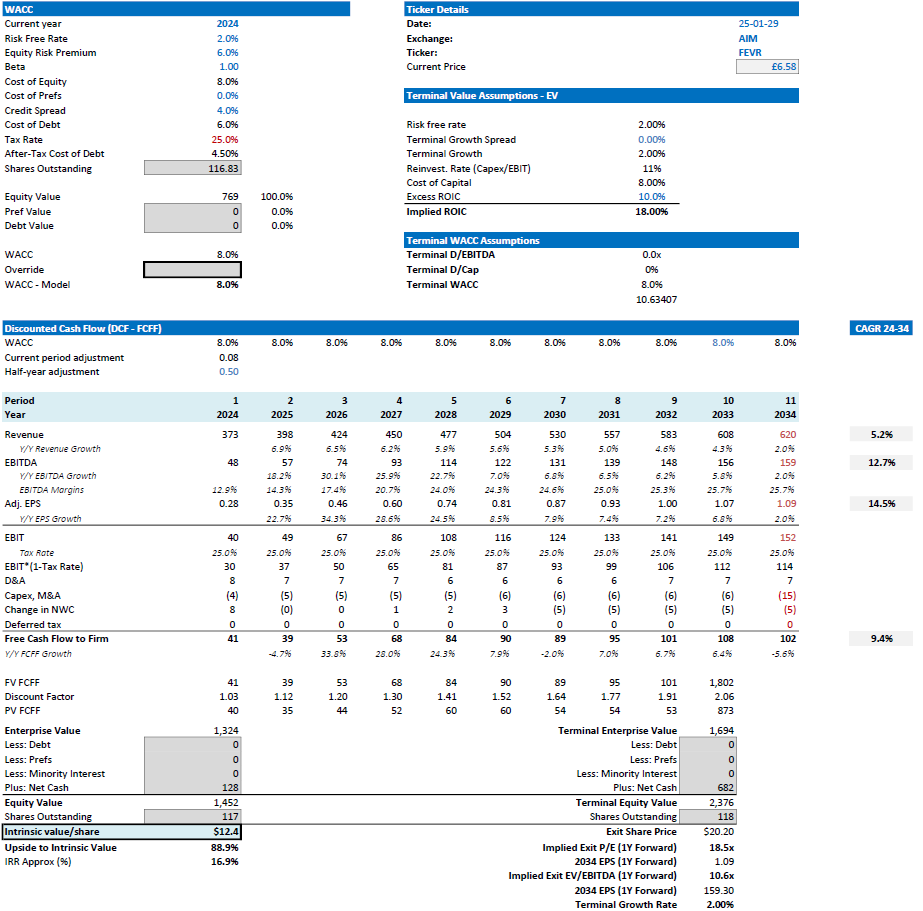

I believe long-term earnings power for the business is misunderstood by the market, and my base-case scenario underwrites more than 85% upside to intrinsic value, assuming terminal EBITDA margins of 28% and an exit multiple of roughly 10.6x EBITDA. My expectations largely differ from consensus for stronger top-line growth, and a belief that margins will revert towards historical levels over the medium term. Downside in the investment is capped by a potential sale to a strategic or financial acquirer.

History

Charles Rolls had a relatively average resumé up until the age of 40. That’s when he quit the consulting business, liquidated his life savings, and raised capital from a few parties to purchase Plymouth Gin. With no industry experience and a reliance on an instinctive gut feeling that he could turn the business around, he pushed forward. To my mind, this doesn’t belong in the calculated risk category. He just went all in, and the odds of succeeding were steep.

Rolls bought the UK company for £500,000. The firm was bleeding about £25,000 per month, while the marketing budget was approximately £100,000 per year. For that price, he got a brand, but one that was out of favour. After getting into the business, his first steps were to arrive at a major bookstore in London and begin reading everything he could about the alcohol industry—quite literally sitting on the floor reading books. What he lacked in experience, he made up for in focus and a beginner’s mindset.

Fortunately, I knew nothing . . . . Sometimes it’s an advantage not to know anything about a business. I had no relevant experience. (Charles Rolls )

With the cash burn continuing, Charles felt ample pressure to turn the business around. He began cold-calling customers and depleting inventory to raise cash. This bought Charles some incremental time and some breathing room that allowed him to experiment with a refreshed bottle design, alcohol content, and flavour recipes. With enough experimentation, he was able to develop a recipe that made the brand popular again. Sales grew 1300% over the next four years, and the business was eventually sold for £28 million—a tidy profit, I’d say.

Rolls wasn’t one to sit tight, though. In 2004, he partnered with Tim Warrilow, an industry consultant, to create a new gin to capitalize on premiumization trends. But Charles’s industry experience led to the insight that no matter how good the gin, it was always being diluted with mediocre tonics. He remembered doing taste tests in the United States in April 2000, with each tonic being “far too sweet, had far too little quinine, and they tasted of grapefruit.” As a result, they pivoted their efforts toward creating a premium mixer.

The strategy for the new product was set—create a premium mixer using natural, high-quality ingredients, and avoid the use of artificial flavours or sweeteners. They determined that sourcing the best ingredients from around the world was going to be a key differentiator. This led them to travel as far as the Democratic Republic of the Congo to source the best quinine available in the marketplace. Applying this artisanal approach and maintaining high standards for the product were how they eventually created the premium mixer category. The first tonic water was ultimately developed after working with ingredient specialists for about two years.

Fever-Tree was now born. The name originated from the chinchona tree, which is well known for producing quinine. This ingredient was historically used to treat malaria, which typically causes a fever. As quinine is very bitter, it was then mixed with sugar, water, lime, and gin to make it more palatable. Charles and Tim chose the name to emphasize its focus on high-quality ingredients and historical origins.

Business Model

Fever-Tree probably has the most simplistic business model of any company I’ve researched. They simply source and buy ingredients, market the products, and reinvest into new products. All distribution and production is outsourced to regional partners and bottlers. The business has very few tangible assets and little to no capital expenditures. The only exception to this occurs when Fever-Tree is required to purchase and own custom bottles in select markets to meet regional recycling and reuse requirements.

The company sells products through two channels: on-trade, which includes bars, restaurants, hotels, nightclubs, and cafés; and off-trade, which includes supermarkets, liquor stores, convenience stores, and online retailers. Both channels are ultimately important, although Fever-Tree has prioritized the on-trade channel, as they have found this the optimal approach to creating brand value in the minds of consumers.

In the on-trade channel, consumption is near immediate. The cocktail is prepared by professionals who usually have a full repertoire and access to ingredients that individuals are unlikely to have at home. To grow in this channel, Fever-Tree invests significantly in personnel who work with bars and restaurants to get the product onto menus. As such, tastings and industry events are the best way to find new accounts. From what I gather, once they make it onto a cocktail menu, they’re rarely displaced. The caveat is that these customers generally use only a fraction of the mixers in the portfolio, as space behind the bar is limited. Winning over key gatekeepers like chefs and bartenders is essential, as this is usually the path by which consumers discover the product.

The off-trade channel operates contrary to most of the on-trade characteristics. Here, the cocktail is prepared by an individual at home, who will normally lack the depth of ingredients otherwise available in a typical bar. This limit of ingredients at home is a huge barrier to preparing cocktails—survey s have shown that as the number of ingredients goes up, the probability that a consumer will make the actual drink goes down exponentially. This makes the time savings and quality characteristics of Fever-Tree’s product more important. In the off-trade channel, consumers will be drawn to the products that are promoted or bundled or where they have prior awareness of the brand. It seems that competition in this channel should be higher, as new brands and private-label products will increasingly emerge. So, while the off-trade market is likely many times the size of on-trade, higher competition and easier price comparisons likely make the economics in this channel modestly worse.

Segments

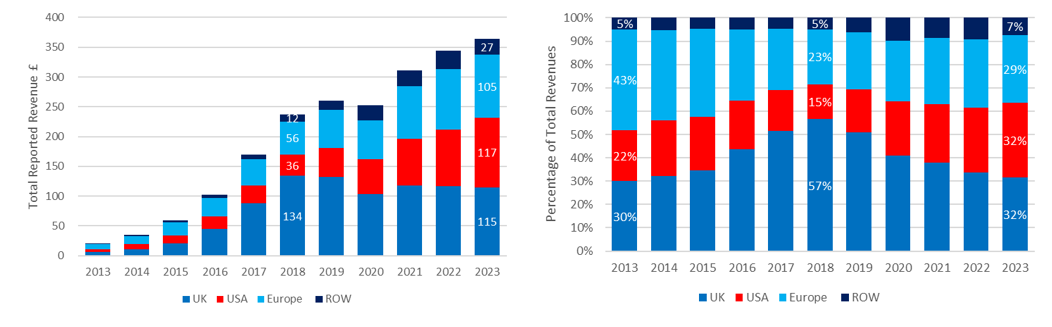

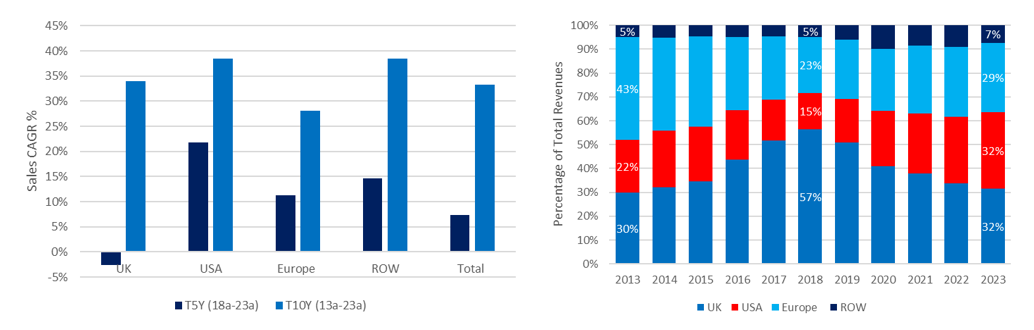

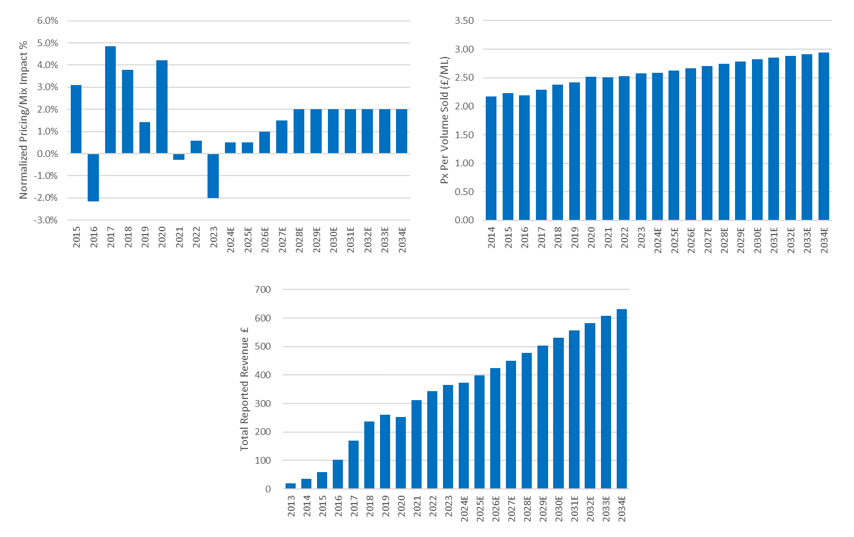

Fever-Tree holds the leading position in the premium carbonated mixer market globally. Given the firm’s origins, the United Kingdom represented the largest portion of their sales until 2023, when the United States grew to become the largest market. As shown below on a group basis, sales grew at a 33% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) from 2013 to 2023, a first-rate performance, in my view.

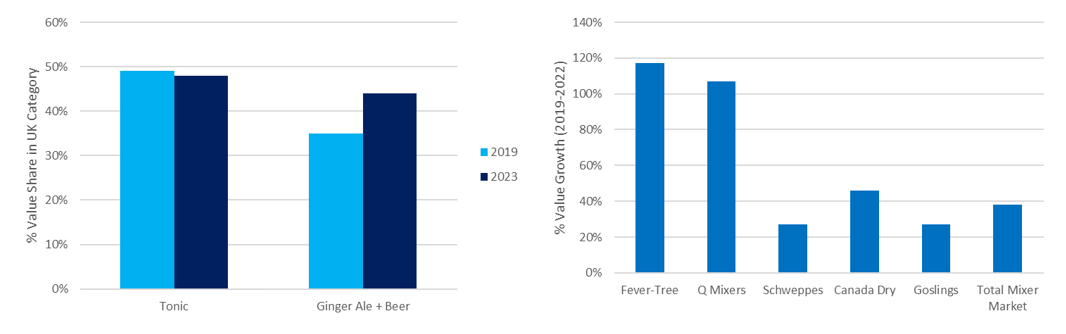

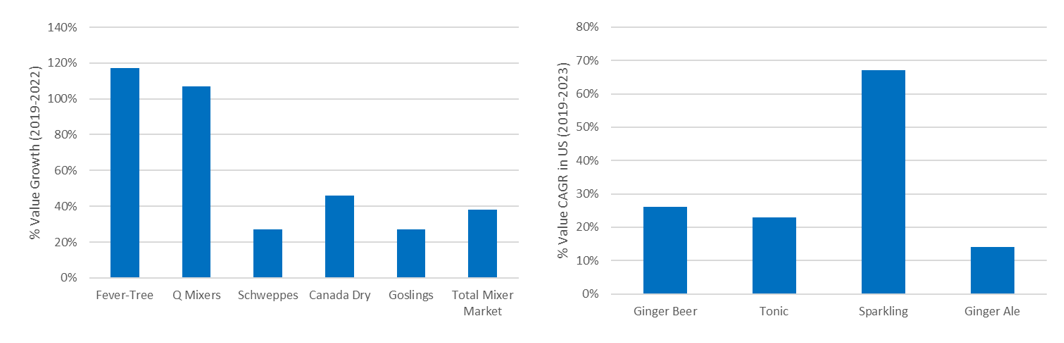

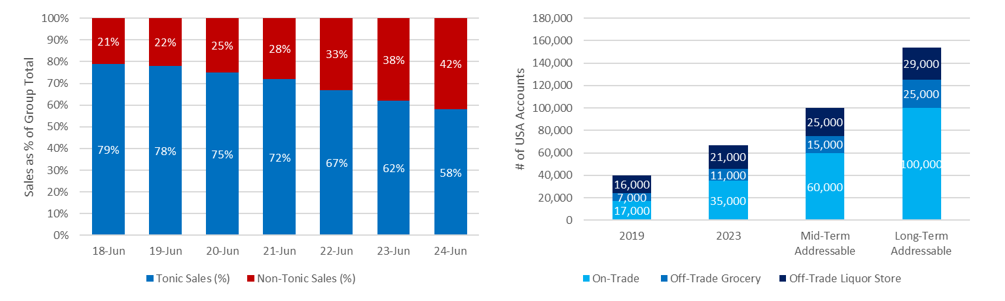

UK sales have grown at a 34% CAGR since 2013 but peaked in 2018 in value terms—coinciding with the gin boom in this market. The number of gin brands exploded during this period. Spirits Beacon, an industry publication, called it the most competitive gin market in the world. This illustrates that Fever-Tree can do well when the adjacent category is prospering too. Gin more than doubled its market share relative to other liquors over the four-year period ending 2018. Given its leading position in mixers and weaker competition from largely just Schweppes and Fentimans, Fever-Tree was able to grow roughly 12x from 2014 to 2018. Subsequently, the momentum slowed in the gin market and shifted toward other spirits. Another headwind has been the weaker consumer, which led to sales falling at a 3% CAGR from 2018 to 2023. However, the brand position has remained strong, with the Tonic value share at 48% in 2023 and Ginger Ale + Beer value share at 44%, up 9% since 2019, as shown below in Figure AB. On-trade penetration also continued to grow to over 60%, up 10 points since 2019. The consensus seems to be that this market has largely matured, and I tend to agree. While prior momentum is unlikely to be repeated, there is ample evidence that Fever-Tree is maturing with a healthy and profitable position in this market. Future growth will be mostly driven by non-tonic products and modest pricing—and that seems just fine to me.

Next up is the US market, which is by far the biggest opportunity for the company over the medium term. While US and UK sales for Fever-Tree reached a similar level of sales in 2023, the total amount of spirits consumed in the United States is approximately 12x higher. However, a much larger proportion of spirits consumed in the United States are dark spirits, which are largely consumed neat (i.e., at room temperature with no ice or mixer) or on the rocks (i.e., with ice only). This makes the market opportunity larger but far less than the 12x figure management alludes to. The premium mixer market is also much smaller in the United States, representing 10% to 12% of the category versus roughly 50% in the United Kingdom. This implies ample growth opportunity and material room for Fever-Tree and their competitors to grow over time. As shown below in Figure AC, trailing three-year and four-year trends into 2022 and 2023 highlight that Fever-Tree has been growing at attractive absolute rates and well ahead of the total mixer market.

As the data above shows, the strongest growth rates achieved for different parts of the US portfolio were mostly ex-tonic. This is critical and, in my opinion, kills one of the recurring bear theses on the stock—that the company is too skewed to tonic and won’t have success outside this category. Figure AD below shows this as largely a historical artifact when UK gin trends were supercharged for a period. As of mid-2024, 42% of the portfolio was non-tonics, and indications are that this will likely grow over time. In the United States, only about 33% of the portfolio is tonics, roughly 45% is gingers (ale and beers), 10% is sparkling (pink lemonade, etc.), and 12% is other (margarita, etc.). In the United States, Fever-Tree has built lots of momentum excluding tonic, with new launches that have included a sparkling pink grapefruit, sparkling lime and yuzu, and blood orange ginger beer. Each of these was crafted to pair with spirits other than gin. Sales from cocktail mixers like margarita and Bloody Mary have also grown from a very small base, and the market opportunity here is huge in the United States, as the margarita is the most popular drink in 40 states. From a penetration perspective, we’re still in early stages—management sees an opportunity to more than double the number of accounts selling Fever-Tree products over time, with liquor stores and on-trade accounts being the biggest opportunities going forward. Sustained innovation and new product launches to meet local market needs will be instrumental in achieving their mid-term and long-term ambitions in the United States.

The European segment generated £105 million in sales in 2023, growing at a 28% CAGR from 2013. Today it’s the third-largest segment. According to Nielsen data, Fever-Tree is the number one mixer brand in Europe. On a trailing five-year basis, they delivered an 11% CAGR—with performance driven by share gains in the premium mixer market and strong gingers product growth. Management has identified three markets where they are mature, five that are still growing attractively, and three (France, Sweden, and the Netherlands) where they are in very early stages of growth. Each country tends to have different distribution relationships, and it appears that at least a handful of the initial partners Fever-Tree found weren’t allowing the business to reach its potential. This led to distribution partner changes in markets like France and Greece in 2023. However, even with these non-optimal partners, they were able to deliver growth value share in the premium category and outgrow both tonic and ginger beer markets into 2023. Ongoing brand investments in each of these markets have continued to drive more awareness of the product as well as its artisanal, quality-ingredients positioning. Fever-Tree management had previously set a target to grow this segment 2.5x the 2020 base of £65 million over the medium term. I think this should be achievable over the next three to five years due to the brand investment and improved distribution power.

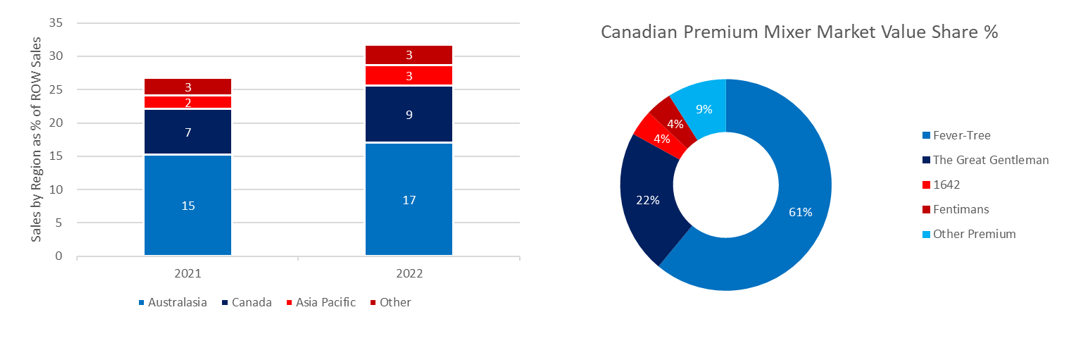

The rest of the world (ROW) segment has delivered great performance, growing at a 39% CAGR from 2013 and a 15% CAGR from 2018. As shown below, Australasia generated the bulk of sales, at 54% in 2021 and 47% in 2022. Canada was the next largest, generating sales at about half that level, at 25% to 27% of segment sales. The remaining 18% to 20% of sales account for all sales in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, etc. Akin to its approach in many European markets, Fever-Tree is also going through an investment cycle, hiring more local talent and switching distribution partners to hopefully drive better growth and profitability. They are also aiming to localize production in Australia, which at some point in the future will help support broader Australasia growth. In Canada, trends appear solid, and a new distribution partner (Tree of Life) has added approximately 2,500 distribution points at major retailers in the country. In Canada, they dominate the mixer category, like in the United Kingdom, with 61% of value share, and they have grown at 6x the rate of the next-largest brand (The Great Gentleman). As shown below in Figure AE, they were also the number one ginger beer brand by value in Canada in 2023.

Despite a huge total addressable market (TAM) potential and a rapidly growing middle class in Asia, this opportunity is rarely discussed. I’m not sure why management hasn’t spent more time on this opportunity or, if they have, why they haven’t been able to scale up the business in this region. The only area discussed by management is the partnership with Asahi in Japan, which has helped them with distribution and a better understanding of the Japanese market. However, excluding some on-trade wins with hotels/bars in larger cities, I’ve only heard anecdata on the opportunities or challenges. It’s fair, though, as it falls very low on the materiality threshold today, but this will hopefully change over time. At this point, it appears that the premium mixer category is in its infancy in the Asia and Other segments, and substantial brand investments are likely required to grow the category in the same fashion as in the other regions.

Excluding the United Kingdom, each of the segments seems far from mature, and there is good evidence that the brand continues to mature well as the premium category grows in value in more markets around the world. This won’t happen with just any brand, but Fever-Tree has done it so far.

Industry Trends

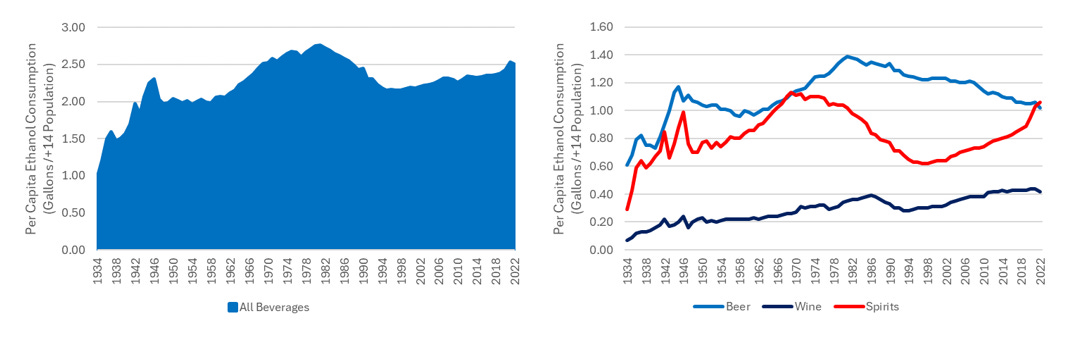

Fever-Tree has positioned itself favourably vis-à-vis two major trends: the growth of spirits relative to other alcohol and the premiumization of alcohol. Data from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) covering the US market shown below illustrates that total per capita ethanol consumption has grown at about 0.7% CAGR from 1998 to 2022. Aggregate ethanol consumption trends in the United States have been relatively stable over the longer term. However, mix shifts among the categories have led to considerably different CAGRs, with spirits at +2.7%, wine at +1.7%, and beer declining at a -0.9% CAGR. Notably, in 2022, spirits consumption in the United States exceeded beer consumption for the first time since the late 1960s. The popularity of cocktails and an increasing awareness of the calorie content of different beverages have driven more consumers to choose spirits as their choix du jour. Going for beers isn’t quite as popular as it used to be.

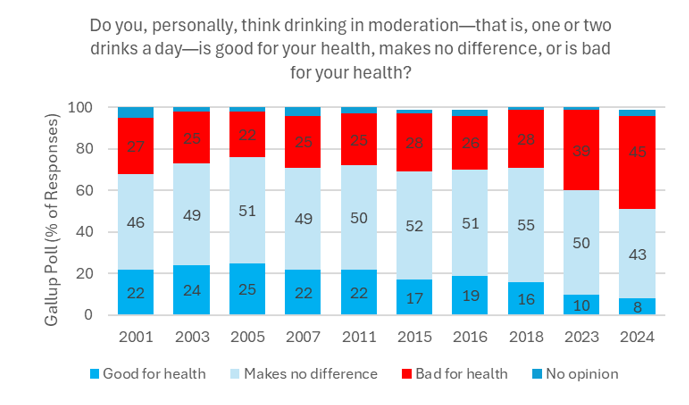

Historical trends have favoured spirits, and I get the sense that these will persist. However, the alcohol industry also has several overhangs today. The first is that demographics are shifting unfavourably—baby boomers are coming off peak years of consumption, and young cohorts of the population are drinking both less frequently and in less volume. The Cleveland Clinic highlighted that adults born after 1997 drank 20% less than millennials, and 28% to 30% just outright abstained from alcohol. But the definitive reasons as to why this was happening were somewhat elusive. Some theories include a greater awareness and prioritization of health, impacts on weight gain, growth/consumption of cannabis, and shifts in ethnicity mix. My take is that it’s probably a combination of all the above. Figure AG shows a Gallup poll illustrating the idea that consumer perception has outright changed too—in the early 2000s, about 25% of respondents believed that alcohol was simply bad for your health, and that figure jumped to 45% by mid-2024. Even the World Health Organization began saying in late 2022 that “when it comes to alcohol consumption, there is no safe amount that does not affect health.” Most people reading this might remember when one glass of wine per day was considered healthy, but now at least a few studies have shown a clearer link between cancer and drinking alcohol. In 2025, the bad news on this front continued, with the US Surgeon General coming out with a report reiterating this theme. However, some people believe this analysis is flawed, as it views the relationship linearly and not exponentially—the higher rates of cancer are much more skewed toward individuals who are heavy drinkers, not low or moderate drinkers (I.E less than 2 drinks), which wasn’t explained well in the initial report. Whether the analysis is 100% correct or not, it is bad press. The possibility that all alcohol will have warning labels at some point in the future seems to be growing. Given that context, it isn’t surprising that no-alcohol drink versions have continued to grow above the industry. In the United States, no-alcohol volumes grew 29% in 2023 over 2022, and even the low-alcohol category grew at 7% versus US spirits volume, which fell by 3.4% year over year in 2023. I think demographic headwinds could persist, but the above suggests that incremental growth will be just harder rather than their having to cope with an instantaneous step down in volumes.

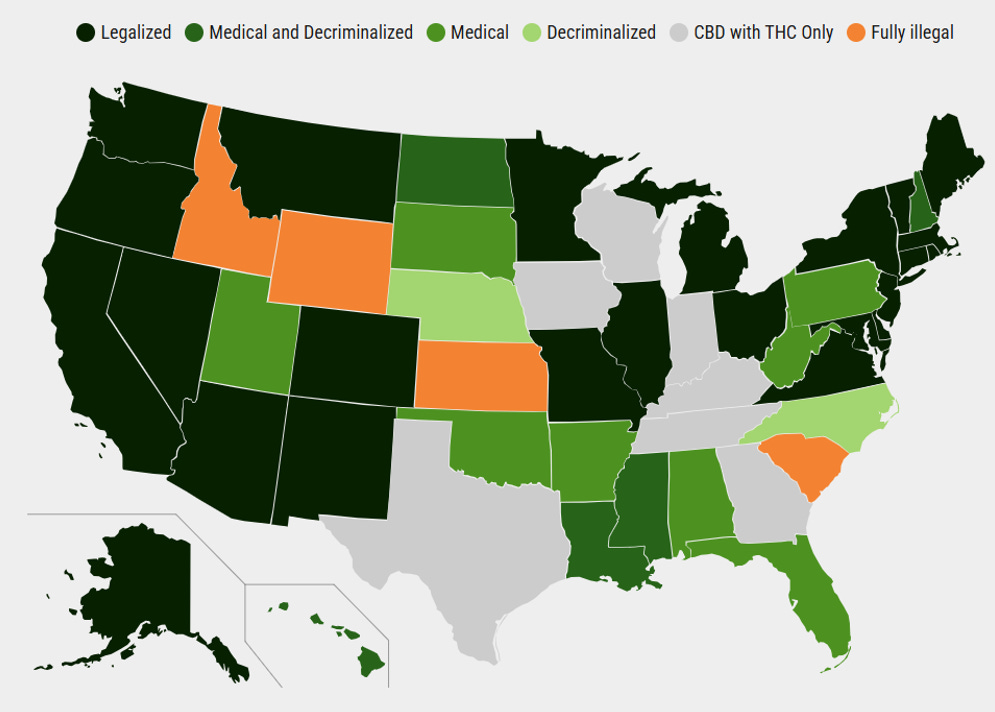

The second threat, at least in some ways, has been the emergence of marijuana. As of August 2024, about 24 states have legalized consumption (38 for medical use), which has supported the proliferation of the variety of consumption formats, including vapes, edibles, and beverages. An IWSR report highlighted that about two-thirds of cannabis users consumed alcohol but that only one-third of cannabis users consumed alcohol. This overlap in the customer base makes it enough of a potential source of risk. Marijuana users also tend to skew younger, so impacts from this might not be entirely apparent until a few years down the road. According to a study released in 2024, from 1992 to 2022 there was a 15x increase in the per capita daily consumption of cannabis. This study also showed that daily consumption of cannabis exceeded daily alcohol consumption for the first time on record—17.7 million people used cannabis daily in 2022, but only 14.7 million people used alcohol daily. Even frequency was four to five days per month for the average drinker but 15 to 16 days per month for the median cannabis user. Overall, I believe that over time, competition for consumer spending will grow, but at this point there appears to be limited evidence that this is currently leading to a step-down in alcohol consumption.

The third threat facing the industry today is that in many regions the consumer is relatively strained. This is most evident in the United Kingdom and the United States, where food, energy, and housing costs have grown, limiting the availability of cash for more discretionary categories. Also, looking at spirits volumes in the United States, they peaked during the COVID-19 pandemic and have remained under pressure for two consecutive years. I believe 2024 has not seen much growth, and growth in 2025 seems unlikely from my perspective. Even the entire premium part of the market declined for the first time since 2009. I think the headwinds from a weaker consumer will be a cyclical and relatively short-term challenge, while the former two risks will persist over the long term.

The fourth threat facing the industry today is the emergence of GLP-1s. This medication appears to discourage appetite for alcohol. In early 2024, NIAAA and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) as well as parties from the Scripps Research Institute found that Semaglutide reduced alcohol consumption and binge-like drinking in rodents, which sometimes, but not always, has a relationship with how humans react. My understanding is that when an individual takes GLP-1s, they feel fuller and more satiated, which translates into less food and beverage consumption. An estimated one in 10 people have alcohol use disorder (AUD) in the United States, and they likely account for a disproportionate amount of lower-priced volumes. Of all the risks, this seems to be the biggest challenge for the alcohol industry, but still in the very early stages as to how exactly this will play out. The main mitigating factor here is that while >40% of the US is obese, this figure is much lower globally at about 16%. The potential impacts will be skewed to the US market where incomes are higher, and obesity rates are higher. To tie it all together, the industry is facing some cyclical and potential secular headwinds. But it appears Fever-Tree isn’t as directly exposed and will be able to manage successfully through these challenges.

Competitive Advantage

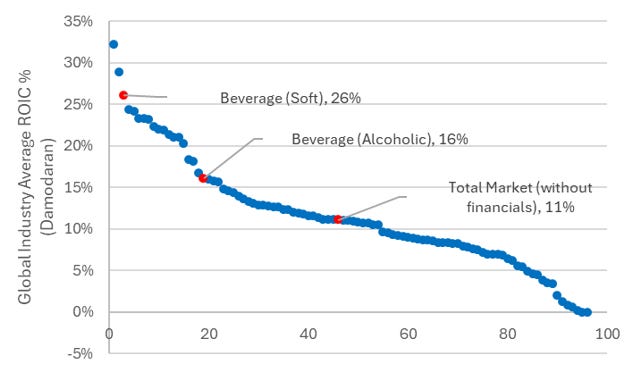

The soft drink and alcohol industries have generated superior market returns for a long time. This is due to robust competitive advantages largely driven by scale. Figure AI below highlights that the soft drink industry generates an average return on invested capital (ROIC) of roughly 250% of the market average, and alcohol producers generate about 50% better returns than the market. This category performance is largely driven by a few giants like Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Diageo, and Brown Forman. That’s even with competition still thriving for the most part in each category. The biggest factor seems to be that once an operator can reach enough scale, they can reap benefits from operating efficiencies (higher levels of utilization), procurement, brand investments, distribution, and customer loyalty. Smaller players are unable to capture similar benefits on a global basis.

Fever-Tree benefits from all these drivers except for operating efficiencies, as they utilize an outsourced product and bottling model. They can, however, use their scale to purchase the highest-quality ingredients around the world. One example I learned of from an employee was that most/all the water for the UK-produced product is sourced from a bore hole (well) that has very low levels of minerality—which is important, as higher-minerality water interacts differently with liquors. The emphasis on quality ingredients seems very genuine to me. Ingredients for some of the ginger products they produce are sourced from the Ivory Coast, India, and Nigeria. Only lemons from Sicily are used, yielding a distinct flavour. Even the extraction of flavours and scents uses a method typically utilized only by perfumers. My guess is that most of these higher-quality ingredients aren’t as easily available from flavour laboratories used by their competitors, who therefore face a hurdle to producing the same type of high-quality product.

The company also benefits from a first-mover advantage. This is most true for on-trade relationships, where shelf space for mixers is very small. Once a product is on a menu, any product attempting to replace it needs to win over chefs/bartenders and drive either lower costs for them or provide an ability to charge more for the final cocktail. Larger scale in bigger markets also translates into an ability to partner with and fulfill the needs of national hotel or restaurant chains that are looking for a premium mixer to add to a menu. Off-trade, the benefits of scale largely allow Fever-Tree to experiment with a wider range of promotions and formats that would meet consumer needs. Prior expert interviews have also highlighted that the strength of their portfolio often leads their products to be sold in entirely different sections of a grocery store than other mixers. The ideal situation for Fever-Tree would be to be placed away from low-quality products, where price comparisons are more likely to come to mind, and close enough to the liquor section that consumers can easily see an opportunity to pair the product.

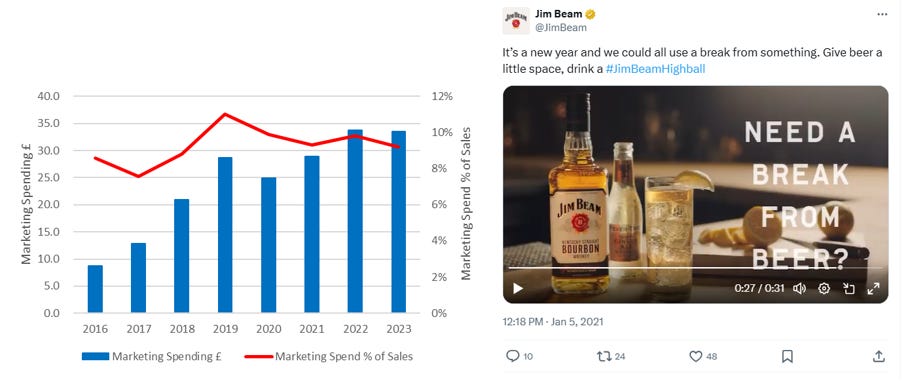

Another area where Fever-Tree derives some competitive advantage is in its ability to scale its brand and marketing spending. Historically, the business has utilized several historical partnerships with spirits companies to drive sales. For example, the partnership in the United States with Jim Beam has been mutually positive, as Fever-Tree gets leverage on Jim Beam’s regional market awareness but also expands the number of consumers who will consume the liquor (i.e., not everyone will drink Jim Beam neat or on the rocks). Whether or not #JimBeamHighball is a secular trend, I think this shows the power of working with partners who are having their own success. Fever-Tree can then adapt the portfolio to meet any areas that are cyclically strong or weak. Figure AJ below shows the consistent growth in investment in marketing on the portfolio and reasonable consistency as a percentage of sales. Fever-Tree has also invested selectively to sponsor sporting events in cricket, tennis, and golf, which are a good overlap for the target consumer. By my account, they have some competitive advantages in terms of brand, procurement, and scale, and the stability of their market share and leading market position suggests that they remain in an enviable position.

Competitive Landscape

Schweppes has historically dominated the tonic water market. Like for many incumbents, innovation and nurturing of the brand and portfolio are secondary considerations when you are a dominant player. Looking at the Schweppes packaging below in Figure AK, one can see it hardly gives off an image of a premium or unique product. Keurig Dr Pepper, the Schweppes parent company, appears to have bigger focus areas, including coffee, soft drinks, and healthier beverages. With over US$100 million in sales coming from the Schweppes brand and the portfolio generating approximately US$15 billion in sales, it’s easy to understand how a nimbler, innovative firm was able to beat them in this area. By late 2017, they introduced a premium product branded as Schweppes 1783 to compete directly with Fever-Tree and with similar positioning—a new smaller premium bottle, new flavours, and craft-ingredient positioning. However, I don’t believe this offering has impacted Fever-Tree much, if at all—product placement in retail stores appears to be subpar, and far as I know, they have invested very little to build on trade relationships, which are hugely important in this category.

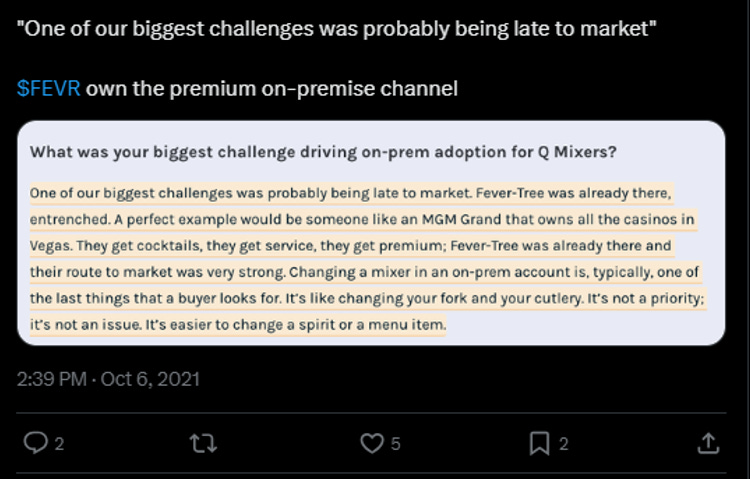

Q Mixers is the company’s main premium competitor. The founding story of Q Mixers is actually relatively similar to that of Fever-Tree—the idea was to create a better-quality tonic to mix with premium gins. Instead of going to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to source gin, they went south to Peru. The initial sales were into top-tier restaurants like Gramercy Tavern and Milk ’N Honey. On the retail side, they first sold to Dean & DeLuca and Whole Foods but eventually diversified to many large grocers and retailers like Kroger. Q Mixers’ distribution partner is Breakthru Beverages, which I believe is the second largest in the United States and has less scale than Fever-Tree’s partner Southern Glazer’s. While it’s hard to get a ton of details on the business, it appears that production is localized in the United Sttes, they have less global scale, they have invested less into on-trade channels, and they have a weaker distribution partner—all things that tip the scales in Fever-Tree’s favour. Figure AL below is an excerpt from an InPractise interview that highlights how being late to the market has been the biggest challenge for Fever-Tree.

Q Mixers has been the only real competitor for Fever-Tree in most regions around the world. However, after 17 years of running the business, they have had to tap investors for seven rounds of capital—far more than Fever-Tree. While I’m not entirely certain what they used the proceeds for, it appears that internal turmoil or financial pressures drove the need for external capital. This likely impaired their ability to reinvest to support their brand during the past few years or get into on-trade distribution. They even replaced their CEO in late 2024, indicating that some of my suspicions may be correct. The new CEO, Betsy Frost, joined in late 2024, but her experience skews toward consumer packaged goods (CPGs), and the lack of alcohol-industry experience seems like a clear negative. The risk of a future mistep or pivots in strategy seems higher—but perhaps they will finally invest more into on-trade opportunities creating incremental competitive pressure on Fever-Tree.

Despite some competition in the premium category, if I add up the combined market share of Fever-Tree and Q Mixers, it’s estimated to be about 88% to 90%. With a duopoly-like market structure and their biggest real competitors being Canada Dry and Schweppes, I don’t think competition in the category is nearly as high in reality as is feared by the market. This is most easy to envision in the on-trade market—if you are first onto a menu, you’re unlikely to get displaced, and if a premium offering isn’t on the menu yet, your real competition is the soda gun. Executives from Fever-Tree have said in the past that the true costs of a soda gun are actually much higher than most operators realize. This is due to maintenance costs, equipment costs, and syrup bags, which are rarely replaced as they hit expiry. I’m not so sure I buy into this idea, but for an upscale restaurant or hotel, I can see how these soda guns could be replaced with a premium offering

Off-trade, the market seems at least somewhat more competitive given the different dynamics—see Figure AM below showing an aisle from a specialty retailer in my neighbourhood. This shows that a handful of regional or local brands should be able to create a similar product in many cases, and I think it’s even possible that they have modest scale in their local markets. However, without the distribution power that Fever-Tree or Q Mixers has secured, I don’t think any will really be able to scale up to comparable levels, especially if they are not willing to invest into the on-trade channel. Fever-Tree’s continual investment into on-trade through pop-ups, on-trade workshops, special events, and media have differentiated their positioning. Industry sources like Drinks International’s annual brand ranking also corroborate this view—Fever-Tree ranked number one as the best-selling and best-trending mixer for the ninth year running (2023).

Financial Performance

Fever-Tree has delivered great performance in sales growth over the past five- and 10-year periods. The UK segment is an exception to this, but even including the declines from this segment, we have seen about a 7% CAGR on a group basis. From a mix perspective, the United States and United Kingdom were each at 32%, followed by Europe at 29% and ROW at 7% as shown below in Figure AN.

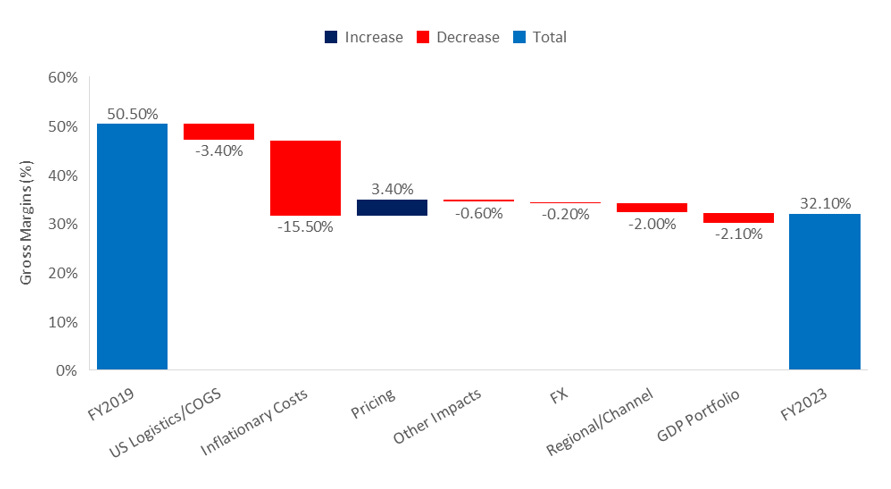

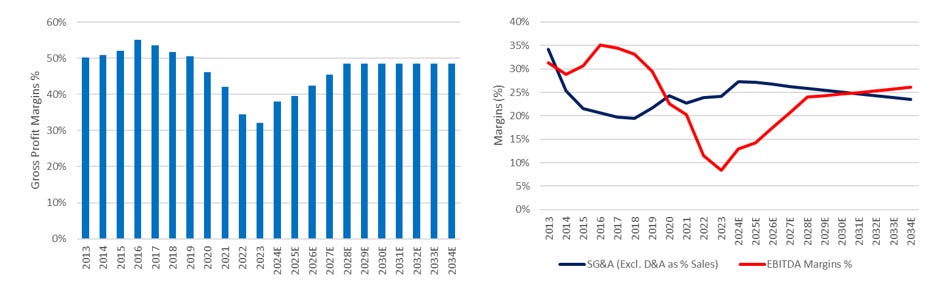

Gross margins historically from 2013 to 2019 were in a relatively tight range of 50% to 53%. However, starting in 2020, the company has seen margins fall each consecutive year due to a variety of contributors, as outlined in Figure AO below. Company disclosures from 2019 to 2023 provide a noisy picture of all the contributors, and some classifications by the company add noise to the analysis—in some years inflationary costs, in others cost of goods sold (COGS), in others specifically the US logistics/COGS. Regardless of attribution, here is how I’d outline the biggest drivers:

Input costs were up meaningfully over the period. This covers sugar, specialty ingredients, labels, energy, and labour. The biggest contributor was higher energy costs in Europe, which directly translate into higher costs for bottles, which are about 30% of product costs and were 80% of total sales. Glass suppliers exacerbated these issues, as they also hedged energy costs in 2023 at elevated pricing following the invasion of Ukraine by Russia while spot pricing subsequently fell, which they didn’t benefit from.

Logistics costs increased substantially in the US market, where demand exceeded available supply. This was due to not renewing its US west coast bottling contract and the fact that additional volumes were not expected to ramp up on the east coast until late in fiscal 2024. This led to the company shipping product from the UK system during a period when sea freight costs were elevated, port congestion or disruptions were more frequent, and driver costs continued to inflate.

Adverse shifts in regional and channel mix represented a roughly 200-basis-point headwind to gross margin (GM). This is a function of selling more into markets with less-favourable pricing. The company also completed a 15% price reset in the United States and introduced a larger format size to increase appeal to US consumers. Fever-Tree’s acquisition of Global Drinks Partnership in Germany also negatively impacted reported margins by about 200 basis points.

Economies of scale outside the United Kingdom were also a headwind, but I’m unsure how this was categorized. The company went from operating a sole bottling plant in 2014–15 to gradually adding a second plant in the United Kingdom for contingency purposes. By 2018, they had expanded to six bottling and canning partners across the United Kingdom and Europe. In 2021, they had a US west coast partner ramp up volumes and in late fiscal 2024 were expected to have localized production in Australia.

The one positive area for the business globally was pricing, which they increased after an extended lag to inflationary costs. Globally they were able to capture pricing in most markets, particularly in Australia, where they shifted their route-to-market approach. The exception to this theme was in the United States, where they were priced at around 4x the level of mainstream brands, but in most other markets globally they were priced at around 2x. This led them to complete a price reset of 15% in 2020, leaving the brand at an approximate 3x premium to mainstream brands.

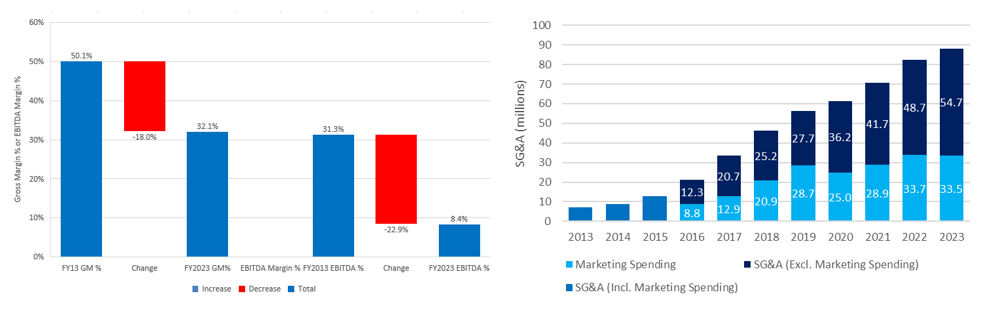

In Figure AP below, I show the GM and EBITDA margin waterfall back to 2013. This shows an 1800-basis-point decline in GM over the period and a 2290-basis-point decline in EBITDA margins. The company has also been shifting away from an agent model in more markets around the world, and hiring in the United States and Europe has accounted for much of the employee growth. Fever-Tree has also expanded from selling into 50 countries in 2014 to more than 85 by 2023. While they have experienced modest deleverage due to operating expense growth, they have continued to generate scale benefits from their marketing spending, which fell from 11% of sales in 2019 to 9.2% in 2023.

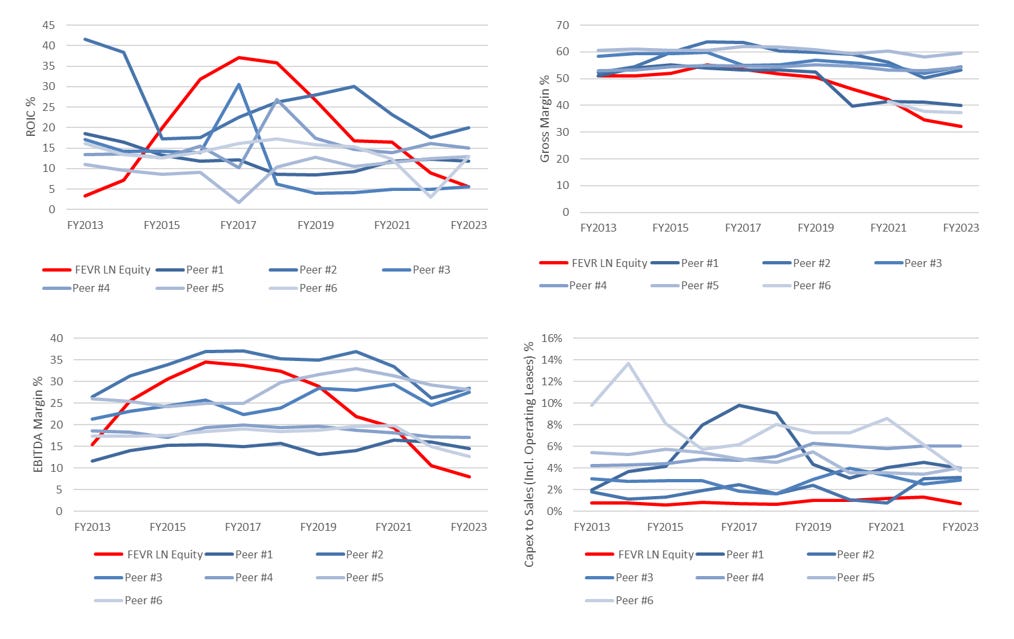

Next, I look at Fever-Tree’s performance relative to peers like Britvic, Monster, Keurig Dr Pepper, Pepsi, Coca-Cola, and Olivi Oyj over the prior decade. In Figure AQ below it shows that for the period from 2015 to 2019, Fever-Tree generated the strongest ROICs in its entire peer group. This was due to its relatively high margin profile and attractive invested capital turnover (high sales versus low invested capital base). However, post-2019, due to falling margins and near doubling of invested capital, they fell to the bottom of their peer group on a ROIC basis. While capital intensity remained very low vis-à-vis the peer group over this period due to the outsourced model, the operating invested capital roughly doubled because of a large increase in working capital and modest growth in property, plant, and equipment (PP&E) (including leases) and intangible assets. This suggests the possibility of generating much higher ROICs than is currently the case if margins can recover. I’ll expand on this later in our report when I review market expectations.

What Do I Think the Market Is Underwriting?

Here I look to adjust all the key drivers for the business to arrive at a fair value estimate close to the current share price. Of course, people will have different expectations than what I’ll outline below, but this is a good tool in thinking about how pessimistic or optimistic the market might be on a particular stock.

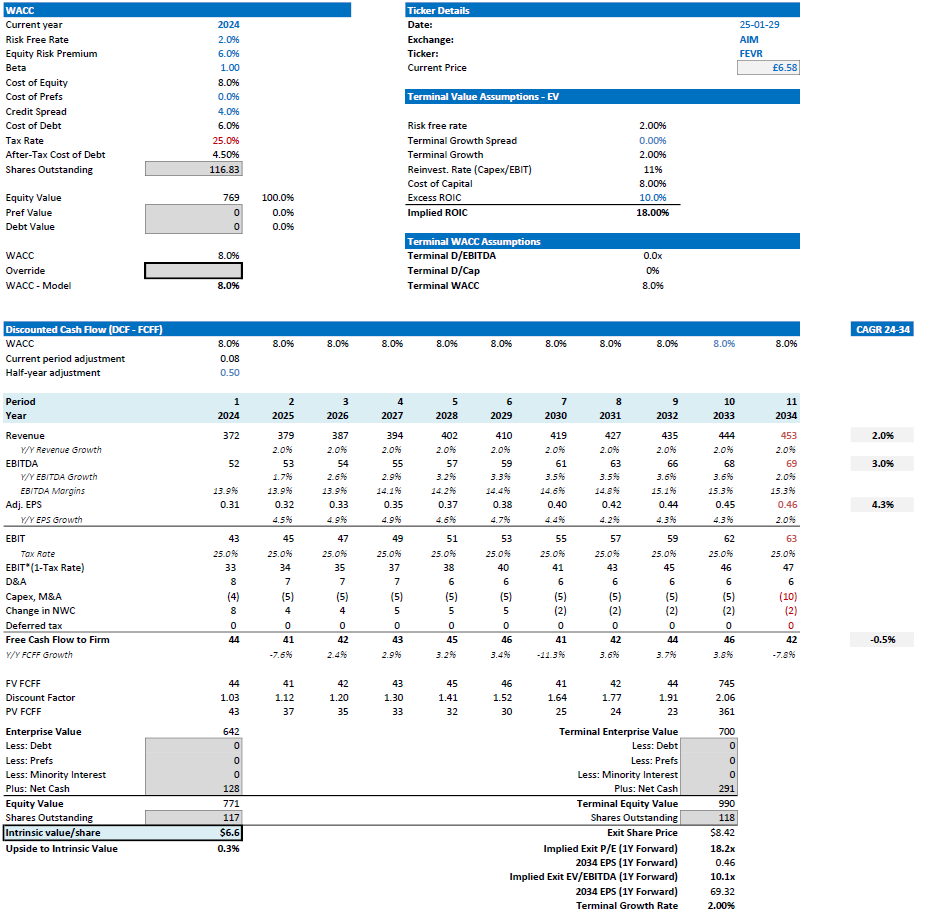

I assume that sales grow at a 2% CAGR over the next decade. This type of performance implies pricing only in line with inflation, which appears overly punitive and makes it impossible to hit management’s sales targets in either Europe or the United States. And the ROW segment remains very small, implying effectively zero success in expansion into Asia over time. The main reason this could occur is if spirits consumption begins to fall more broadly and the company’s success in soda/adjacent categories bears no meaningful sales.

On the margin front, I assume GMs will recover to 39% but will remain at this level over the forecast horizon. This means that raw materials inflation has stepped up and won’t be recaptured by optimization, pricing, or operating leverage. EBITDA margins in this scenario start at the low teens and mature at roughly 15% over the forecast period. Most other assumptions on interest (net cash b/s), CapEx intensity, and working capital changes are otherwise unchanged. In fiscal 2025, this translates into EPS of £0.30, or a P/E multiple of about 21x. On an EV/EBITDA basis, this means a multiple of 12.4x. A snapshot of the discounted cash flow (DCF) output under this scenario is outlined below in Figure AR:

What Do I Feel Comfortable Underwriting?

To start, I think it’s reasonable to assume that consumption of the product will go up on a global basis. There are many countries like the United States, Australia, Canada, and others where premium mixer consumption is still growing, and while that might not be the case in the United Kingdom, this won’t impact results on a total portfolio basis. Finally, wholesale regions like Asia are underdeveloped and should still be a fit for the company’s offerings.

On the pricing front, I do think Fever-Tree will generally be able to increase pricing at least in line with inflation of about 2%, and volume growth of 2% to 3% is very possible as penetration increases. There is some risk that pricing will be skewed to later in the forecast period if a recession occurs, but at this point they have lagged a few competitor actions, so it feels more manageable. The caveat is that many of their competitors have arguably taken price too far, leading to volume declines. I don’t believe Fever-Tree will do the same. Figure AS below shows group revenues growing to about £632 million, a 5.7% CAGR from 2024 to 2034.

Next, on gross margins I expect 600 basis points of improvement in fiscal 2024, in line with management guidance, and subsequent annual improvements driven by lapping elevated glass costs, localizing US production, and pricing. However, due to channel and mix shifts, I expect gross margins to mature at about 48.5% versus historically which averaged 52% from 2013 to 2019. Then, from the perspective of selling, general, and administration expenses (SG&A), I expect management to generate material operating leverage as they lap localization costs. SG&A (excluding D&A) will fall from 27% in 2024 to around 23.5% by 2034. As a result, EBITDA margins will recover to about 26% versus the 2013 to 2019 average of 32%.

I hold capital intensity flat at about 1% such that Fever-Tree spends only £4 million to £6 million in CapEx per year. Recall that this capital is tied to bottles that need to be owned in a few markets. Near term, I expect some work-off of inventories and materials that were built up in recent years, but longer term, net working capital (NWC) remains in line with historical levels. This eventually leads to more than £90 million in free cash flow to the firm (FCFF) in 2029. Cash builds on the balance sheet even after growing dividend payments, and special dividends could likely be issued, as management as done in the past.

I use an 8% cost of equity, a 6% cost of debt, and a 2% terminal growth rate. Despite some potential headwinds for the alcohol industry, I do think the premium mixer industry has some offsetting levers that are underappreciated. A combination of underpenetration of the category/product in major markets, growing spirits volumes, and some pricing power should create a meaningfully larger business over the next decade. Profitable growth should still occur for a very long time—even if the core alcohol market implodes, there is some chance Fever-Tree can pivot more toward premium soft drinks.

My DCF model suggests that fair value using these assumptions is roughly £12 per share, which is more than 85% higher than the current share price. Please see Figure AU for a screenshot of my DCF output.

Management and Governance

Fever-Tree has been implementing the same strategy focused on building up sales in on-trade, gradually scaling up off-trade in new geographies and creating new products to meet local market tastes. This playbook should be able to be replicated for many years. Given the strategy hasn’t changed as co-founder and CEO Tim Warrilow continues to lead the firm. Charles Rolls stepped away from the deputy chairman role in April 2020 and no longer appears to be involved in any meaningful way. They own 4.8% and 4.4% of the firm, respectively. The capital allocation process has been skewed toward just returning capital via dividends, organic investment to grow in new regions, and the rare acquisition. From a capital allocation perspective, in reviewing their history I don’t see any meaningful blunders. The regular and special dividends in the company’s past suggest they are shareholder friendly. One criticism is that they have run the business with far too much cash, and this can be optimized at some point in the future.

From a strategy perspective, the company has used a spirits-led strategy. Key leaders like Charles Gibbs, head of North America, have extensive global experience in the spirits industry, including at Belvedere, MOET Hennessy, and Diageo. The industry knowledge and relationships that individuals like him bring to the table seem to be a differentiator vis-à-vis their peers. Fever-Tree’s approach is more akin to a master distiller, as they are curating ingredients from around the world and are very prioritized on the quality and flavour of the final product. Even a decade-plus experience with a staples business, like the new CEO of Q Mixers has, would not nearly provide the depth and understanding of how particular the alcohol industry is about its ingredients, process, and craftsmanship. Depth on the team and adjacent industry knowledge appears to be at least part of the reason Fever-Tree has grown more successfully. I think this is why they have effectively created the category in multiple markets around the world and are essentially driving the “third wave” in the mixer market.

Next, the incentive plans for executives seem relatively okay. From 2014 to 2017, performance measures for annual bonuses and long-term incentives were based 75% on turnover (sales) and 25% on EBITDA as they prioritized market penetration, profitable growth, and scaling of the business. In 2016, the long-term incentive plan (LTIP) program was adjusted modestly to include malus and clawback provisions in the case of financial misstatements. In 2018, the approach remained relatively unchanged apart from boosting the salaries meaningfully, which were below market level for a company of their size. Incentives were tweaked in 2023, weighting of performance payouts was adjusted to 60% on turnover (sales), 20% on adjusted EBITDA, and 20% on strategic measures (including innovation, margin improvement, and environmental and sustainability targets). While the reinvestment rate into the business is low, a ROIC measure is not as relevant as it could be, but a future addition of return on equity/capital measure would be welcome. All told, alignment seems sufficient, and I don’t see any large red flags.

Key Risks

Industry tailwinds have more recently favoured spirits over other types of alcohol. A reversal of this would create a small number of consumption opportunities for premium mixer brands like Fever-Tree. Consumer sentiment has changed in recent years, and the addition of warning labels could meaningfully change volume trends in the industry. A consumer shift toward marijuana and away from alcohol globally could also pressure liquor consumption.

Expansion into adjacent areas may spark a more competitive response from large soft drink manufacturers. While Coke and Pepsi seem very unlikely to devote the resources necessary to create a premium product and invest into the on-trade channel, a new upstart could do this in select markets. Seen many times in the liquor industry is a celebrity-backed product aligned with industry trends of low calorie counts and artisan craftsmanship, which could also disrupt the business to an extent. The acquisition of Q Mixers by a more focused entity could also increase competition beyond what we’ve seen historically.

Pricing has been a tailwind for the business since inception, but Fever-Tree’s ability to increase future pricing is going to be driven more largely by the behaviour of mainstream brands. Unfortunately, consumers view the Fever-Tree product in relation to other competing mixers and not relative to alcohol pricing. This leaves them more indexed to CPI plus or minus 1% to 3% in markets once the initial premium is established. However, the soft drink/value mixer category has worse pricing dynamics than liquor, which has historically benefited from premiumization trends.

Under a simplified pre-mortem, If I were to lose money on this investment, it would likely have to be because of a combination of all the above-mentioned factors plus an inability to recover gross margins due to more persistent inflation and weaker structural pricing. As I’ve outlined this seems overly punitive given the business’s historical performance and the fact that it is a founder-led business that should be very interested in creating value for itself.

Conclusion

Fever-Tree has continued to build on its premium position in the mixer market. The company has continued to gain or maintain value share in key markets around the world. The frequency of consumption and loyalty for the brand has continued to grow both on-trade and off-trade. However, a weaker consumer and a strategy to take lower pricing in a higher inflationary environment has weighed on the business. As the consumer rebuilds spending power in the upcoming years and Fever-Tree scales up in key markets, I expect profitability to continue to recover. The founders appear to be aligned with shareholders, and I wouldn’t rule out a potential sale of the business over time. The current P/E multiple of about 19.4x on consensus figures appears high relative to many staples, but as margins normalize, the stock will increasingly look cheap to investors—on my fiscal 2026 numbers, the stock trades at just 13.5x my estimates, and this assumes EPS up only £0.06 from 2021 levels. My base case model can be found below if interested.

As always, if you have any questions or disagree with any of the analysis/views expressed here, please fire away in the comments below. You can also reach me on X/Twitter or icemancapital@gmail.com

Impressive write-up, thanks. And timely! Personally slightly disappointed they connected with Coors, bit down-market compared with them - would have preferred a tie-up with a similar high-end brand.

Does FeverTree have high switching cost? if the answer is NO. then the scale advantage does not exist.